To anyone who considers themselves an original junglist, DJ Crystl needs no introduction. As one of the early pioneers of precisely engineered breakbeat drum patterns that went far beyond the usual amen formula, and dark, yet deeply melodious atmospherics, Daniel Chapman released tracks on DeeJay and Lucky Spin recordings in the early 90s that helped to define the future of jungle and drum and bass for decades to come.

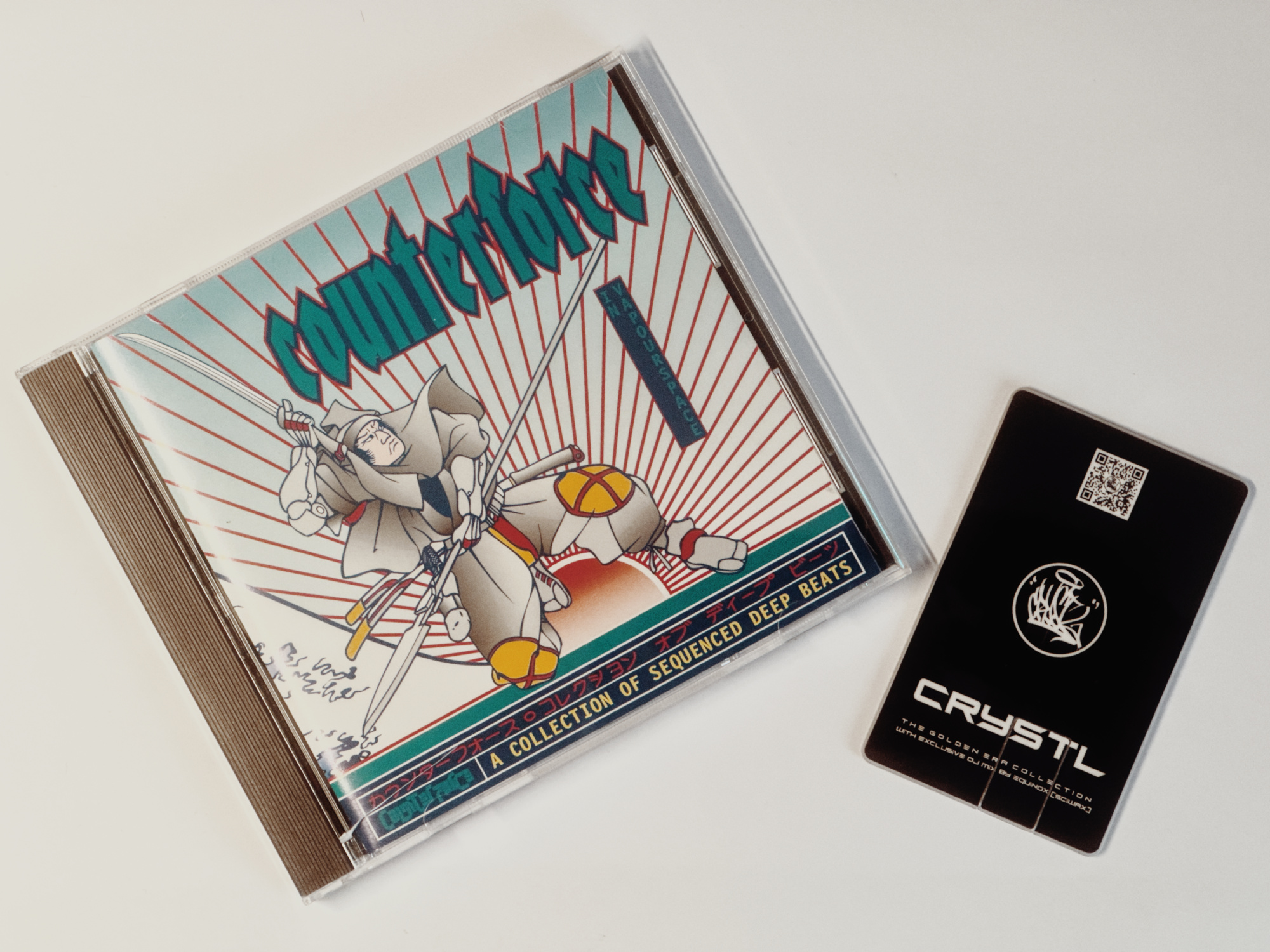

My story with DJ Crystl’s music goes back to secondary school. A classmate lent me a mixed compilation CD called Counterforce (which his elder brother had bought from a man called Horace in Camden Tunes). I was immediately blown away by all of Crystl’s tracks on the CD (Let it Roll, Warpdrive and his remix of A Better Place by Tamsin & Monk). Later, I heard another one of his tracks called ‘The Experience’ on Don FM, released under his MI5 alias.

Although these tracks were one or two years old by the time I had heard them, collectively, they were my soundtrack to the future. I had copied Counterforce onto tape and would spend hours listening to it while sitting on a park bench in Horniman Gardens in Forest Hill, looking into the distance of central London’s skyline (something that also inspired me to get into urban photography several years later).

Tap here to see the Counterforce CD track list.

1 DJ Tamsin & The Monk – A Better Place (DJ Crystl Remix)

2 Hyper On Experienc – Disturbance

3 Goldie – Inner City Life

4 DJ Crystl – Let It Roll

5 DJ Crystl – Warpdrive (Remix)

6 Zero B – Lock Up (Counterforce Remix By DJ Crystl)

7 Lemon D – Deep Space (I See Sunshine) (Drum & Space Mix)

8 DJs Flynn & Flora – Dream Of You

9 DJ Tamsin & The Monk – A Better Place (Bay B Kane Remix)

10 Inna Rhythm – Carrie

11 Koda – The Deep

12 Rogue Unit – Dance Of The Sarooes

13 Orbital – Are We Here?

Over the following years I would try to grab any compilation that included his music, so when DJ Crystl announced that he made available a number of limited edition USB sticks with his entire jungle discography that he personally numbered and signed, I rushed to his Bandcamp page and hit the order button without pausing to think twice.

The USB arrived a few weeks later and did not disappoint. It contains 34 tracks, including all the well-known releases such as Crystlize / Deep Space, The Dark Crystl / Inna Year 3000, Meditation backed with the original, dubplate version of Warpdrive, Paradise / Let It Roll, but also some recently recovered and originally unreleased tracks such as Crystlize 94, Kold Drumz, and DJ Trax’s Slice and Dice Warpdrive remix. It also has an all DJ Crystl mix by Equinox from Scientific Wax, Crystl’s Futurizm atmospheric drum & bass sample pack, and Too Deranged to Meditate, a previously unheard track that Crystl made especially for this project.

The USB also contains a separate folder with high resolution copies of Crystl’s artworks, including the original label for the Meditation / Warpdrive release.

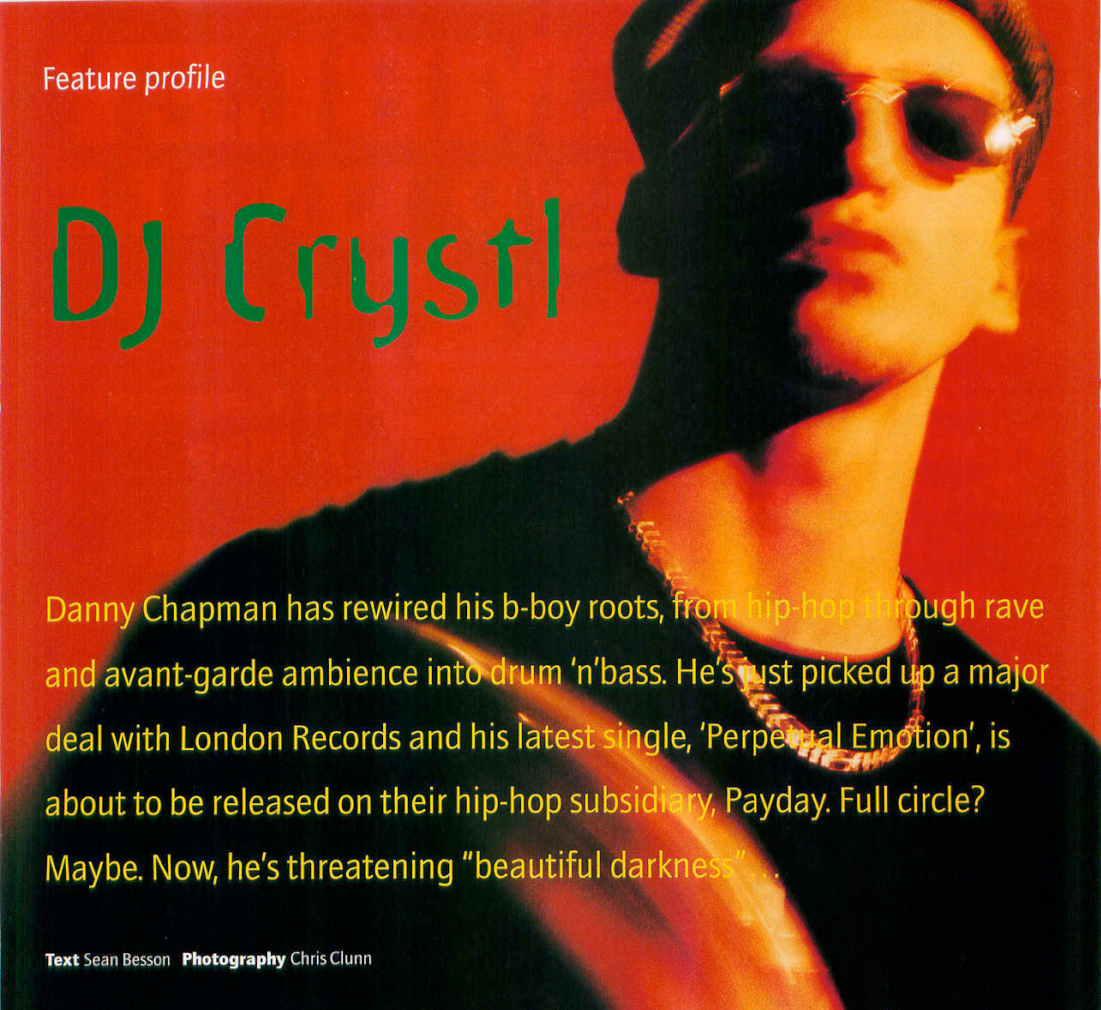

While searching for more background information for this post, I came across an interview with Crystl in the October 1995 issue of the Generator magazine. In this interview, he talks about his early passion for graffiti, b-boyism and hip-hop, and how these later influenced his music. This was fascinating for me to read, because without knowing these details, his records have always felt distinctly urban and metropolis-inspired to me. They resonate with my own perceptions of the city, whether I am surrounded by tower blocks or see graffiti tags when travelling on the Overground.

Tap here to expand inline excerpts from DJ Crystl’s 1995 interview.

It’s all about attention to detail. It’s all about obsession. When Danny Chapman was a kid growing up in North London’s Edgware he decided he was going to be a b-boy. He wasn’t black, he wasn’t American and he wasn’t raised in housing projects. But he got the details right. By the time he was sixteen he had decks, he could scratch mix, he could breakdance and he could spraypaint. He could talk the talk, do the handshake and depending on your point of view he was either fiercely cool or predictably absurd.

“We were our own kind of crew in our area,” recalls Danny, “there weren’t many others. But we knew all the other crews around London and shit. And it was like yeah man this is bad’. We used to go to Covent Garden (a regular breakdancing spot), ride the Metropolitan line, go tagging, bomb train yards (spray them with graffiti) and shit like that man. Everything to do with hip hop we’d do it man. Just checking what was going on, walking down the street, seeing tags, meeting graffiti artists, meeting breakdancers, saying let’s have a battle. I was b-boying in school. I’d take the lino into school and start breaking in the playground at lunchtime. It was mad.”

Seven years later and the teenage b-boy wannabe is best known as 23 year old DJ Crystl and signed to London Records. And DJ Crystl is the cat who sprinkled drum’n’bass with stardust to produce the ambient jungle of cuts like “Meditation ‘Crystlized and ‘Sweet Dreams”. Even the titles were pretty while his soundscapes wers formed from birdsong, waves, weightless girlie sighs, flyaway strings and soft machines. Once again it was about all about detail. About micro edits where sounds morphed in and out of each other while every kick, snare and drum bit was stretched, teased and flexed. Every half-second of every track was a world of mutation and concentration: a place of obsessive sound processing and musical change. Just like a teenage b-boy practising his breaking in front of the mirror: everything is covered. Everything is immaculate. Even when Crystl used to hit the raves there was a part of him that was always sharp, controlled, b-boy, self-consciously cool, whatever.

“I was like the only one of all the people I was raving with that used to dress like a b-boy. I still wore black trainers. I used to dress sensibly with a nice cap and a nice t-shirt. I never used to dress in the stupid clothes the ravers used to wear. I would just enjoy the music and have a laugh. And the best was laughing lat all the ravers out of their faces with their jaws going everywhere but not” he laughs, “noticing my own.”

Once a b-boy always a b-boy perhaps. Like Goldie he enjoys tracing a breakbeat connection from drum n bass into hip hop. It’s an interesting story mainly because it’s not about the evolution of music but a transfer of loyalty. Drum’n’ bass doesn’t depend on KRS-1 or Public Enemy for it’s existence. Instead godfathers of this music are as diverse as LFO (for the sub-bass from ‘LFO’), Meat Beat Manifesto (for the gargantuan breakbeat of Radio Babylon’) and the micro-editing and sound mutation offered by the Apple Mac, the Atari and effects boxes like the Harmoniser. What Goldie and Crystl are talking about is how they map their b-boy sensibilites onto rave and then drum’n bass just as the Goa hippies have locked into and mutated trance.

[…]

“I was so into hip-hop that I used to diss acid,” recalls DJ Crystl. “I hated it. We used to drive around and laugh at people in flares and shit. Just pointing and going ‘Yeah you acid freaks man’. I suppose they were doing that to the hip-hop heads, taking the piss out of us. Fair enough.”

And then Crystl started raving. Like most people he didn’t really know what was going on but a few friends, the sort who get almost messianic about the whole thing, made an effort to take him out and turn him onto the scene.

“A group of my friends who weren’t really into hip-hop that much managed to get into raving, did E’s and everything and as you can guess I got drawn into going. They pulled me to a club and I hated it. I absolutely hated it. I was very suspicious about whether to do E or not. I was like standing next to the speakers going like fucking shut up. The music was doing my head in, everybody was dancing around, treading on my feet and I just got paranoid and claustrophobic. So I went home and put on some hip-hop and felt good.”

But he went out again and eventually he started to enjoy it. “I went to Telepathy and Rage,” smiles Danny, “and to me that’s what did it. I was standing in this club and I started coming up on this E and I heard the maddest, dirtiest drum’n’ bass. And it was just like what it did for me, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I got a wicked buzz and I went another week and another week and it progressed from there.”

[…]

Sometimes house, techno or rave feels like another reality: a form of VR that can only be accessed through taking E. And once you’re in there, locked deep, everything else seems so far away. It’s like you’re becoming a different person. And then you have to decide, especially if you’re an artist, what happens next? How much of vour old self can you incorporate into the new.

“I used to listen to mix tapes,” recalls Crystl. “Micky Finn, Grooverider. I could see the hip-hop element there which is why I liked it as well. I liked the breakbeats and then I heard a couple of hip-hop tracks which I already knew sampled in there. But for a whole year I wasn’t really listening to much hip-hop. In fact, I hated it and couldn’t relate to it. The ecstasy had turned my brain around and fused me onto the rave. I couldn’t relate to the 90bpm speed and rap of hip-hop. It took me a long time to get back into it. It was only when I started getting off the drugs and the E’s that I started getting back into hip-hop again because my mind was free and I had nothing to block it. I carried on raving but then I was listening to hip-hop as well.”

Or read the full interview in the October 1995 issue of Generator here (PDF).

There is so much more I could say about the impact that DJ Crystl’s music has had on me, but for now I will finish this post with an excerpt from DJ Crystl’s interview with Uncle Dugs on Rinse FM earlier this year.

Uncle Dugs: Your style, you know, we’ve all got a ways of describing someone’s style. How I looked at you and even now playing the tunes today, even though it’s 2023, 30 years old, those tunes.

DJ Crystl: That’s nuts, isn’t it?

Uncle Dugs: They still sound futuristic in the sound. Again, like I was saying to Dom, compared to the music of the time, yours both stood out for different reasons. And yours, I looked at, Andy C was doing something similar with the Sour Mash EP at the time. It sounded like it was made like a space film soundtrack, and your music always sounded far ahead of its time, like Bukem’s and people like that for me.

DJ Crystl: Well, he was an inspiration of mine.

Uncle Dugs: He was so good. I didn’t get his music till later down the line […]

DJ Crystl: Especially now with the resurgence of it all, it fits in with everything that’s, I suppose, going on. But yeah, there was no real, again, definitive kind of moment, or I’m going to make it like this. And I suppose it’s the same with every producer, at the time when it’s first time round. You know, maybe more so now trying to be a certain way. I mean, I make it a certain way. But back then, it just progressed into that. And I found myself liking a lot of futuristic sounds. Movies, Blade Runner and all that kind of inspiration, I suppose.

Uncle Dugs: Yeah, you definitely had your own lane. I mean, we just mentioned Brockie when you got here, and give him a shout because I know he’s going to be locked in. But he mentioned one of your tunes as being his favorite tune. And I tell you what I found, because I was a massive Kool FM fan of that time. Proper jungle head, like, couldn’t even look outside of that little bubble. And tunes like, Warpdrive, for instance weren’t necessarily like what were going on, but got battered in the jungle scene. With MCs all going over the top of it passing the mic. And when you think of it, it’s not really that kind of song.